Local dynamics¶

Let us start by restating the constrained time stepping scheme from the previous section

We said, that the equations (58), (59), (60) are solved together, implicitly. In practice, since a solution process may take many iterations, it is often efficient to produce an assembled form of the relationship between \(\mathbf{U}\) and \(\mathbf{R}\), and use it together with \(\mathbf{C}\left(\mathbf{U},\mathbf{R}\right)\), to find reaction forces \(\mathbf{R}\). By substituting (58) into (59) we obtain

and rewrite it as

where

Relation (62) can be called local dynamics, since it relates point forces and (relative) point velocities. \(\mathbf{B}\) can be called local free velocity, since it is a relative local velocity of constraints when no reaction forces are applied. \(\mathbf{W}\) can be called a generalized inverse inertia matrix.

Detailed multi–body notation¶

So far we have presented formulas at certain level of generality. Let us now present detailed multi–body formulas. Let \(\left\{ \mathcal{B}_{i}\right\}\) be a set of bodies and \(\left\{ \mathcal{C}_{\alpha}\right\}\) be a set of local frames. To each local frame \(\mathcal{C}_{\alpha}\) there corresponds a pair of bodies \(\mathcal{B}_{i}\) and \(\mathcal{B}_{j}\). Let \(\mathcal{B}_{j}\) be the body, to which the local frame is attached. \(\mathcal{B}_{j}\) will be called the master in \(\mathcal{C}_{\alpha}\) and denoted by \(\mathcal{M}_{\alpha}\). Consequently, \(\mathcal{B}_{i}\) will be called the slave in \(\mathcal{C}_{\alpha}\) and denoted by \(\mathcal{S}_{\alpha}\). Of course, the choice is arbitrary. Considering evolution of a multi–body system over an interval \(\left[t,t+h\right]\), an analogue of equation (62) can be written down for each of the local frames

where

The above formulae can be conveniently applied in a computer implementation. They stem from the following, juxtaposed algebra of multi–body dynamics. Let \(\mathbf{q}\), \(\mathbf{u}\), \(\mathbf{f}\), \(\mathbf{A}\) gather the suitable vectors and matrices as

To each local frame \(\mathcal{C}_{\alpha}\), there corresponds a block–row of the global \(\mathbf{H}\) operator

where

is evaluated according to one of the specific formulas introduced in the section on constraints.

The \(\mathbf{W}\) matrix¶

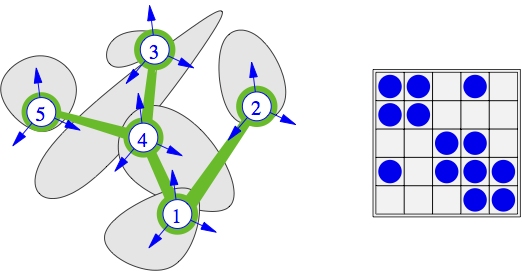

\(\mathbf{W}\) maps local forces into local relative velocities. Algebraically, it is represented by a sparse matrix, composed of dense \(3\times3\) blocks \(\mathbf{W}_{\alpha\beta}\). The sparsity pattern of \(\textbf{ $\mathbf{W}$}\) corresponds to the vertex connectivity in the graph of local frames. Vertices of this graph are the local frames \(\left\{ \mathcal{C}_{\alpha}\right\}\), while the edges comprise a subset of all bodies \(\left\{ \mathcal{B}_{i}\right\}\), such that \(\mathcal{B}_{i}\in\mathcal{C_{\alpha}}\) and \(\mathcal{B}_{i}\in\mathcal{C}_{\beta}\) for \(\alpha\ne\beta\). This has been illustrated in Fig. 6. Operator \(\mathbf{W}\) derives from the formula

where \(\mathbf{A}\) is a \(n\times n\) symmetric and positive definite matrix, and \(\mathbf{H}\) is an \(m\times n\) transformation operator. \(\mathbf{W}\) is an \(m\times m\) symmetric matrix. It is positive definite, provided rows of \(\mathbf{H}\) are linearly independent. This is easiest to see from the flow of the actions in the above formula. A local force \(\mathbf{R}\) is first mapped by \(\mathbf{H}^{T}\) into a generalized force \(\mathbf{r}\). If rows of \(\mathbf{H}\) are not linearly independent, then there exist \(\mathbf{R}_{1}\ne\mathbf{R}_{2}\) such that \(\mathbf{H}^{T}\mathbf{R}_{1}=\mathbf{H}^{T}\mathbf{R}_{2}\) and hence \(\mathbf{W}\) fails to be a bijection. This means, that the null space of \(\mathbf{W}\) is larger than \(\left\{ \mathbf{0}\right\}\), so that \(\mathbf{W}\) is not invertible in the usual sense. \(\mathbf{W}\) becomes singular whenever \(m>n\), which is trivially related to the number of considered bodies relative to the number of constraints. On the other hand, one can always introduce singularity of \(\mathbf{W}\) by using local frames between the same pair of bodies, in such a way that their \(\mathbf{H}\) operators are linearly dependent. This can be related to deformability of kinematic models. For example, the pseudo–rigid body has a linear distribution of the instantaneous velocity over an arbitrary flat surface. Thus, the relative velocity between two bodies over a flat surface is fully parametrized by three points. A larger number of local frames results in the singularity of \(\mathbf{W}\). So does their collinearity. In practice, \(\mathbf{W}\) often becomes numerically singular for many practically encountered configurations of local frames. Indeterminacy of local forces \(\mathbf{R}\) is then an unavoidable consequence of either kinematic simplicity, or geometric complexity, and as such it needs to be accepted in numerical practice.

Fig. 6 A graph of local frames and the corresponding pattern of \(\mathbf{W}\).¶

Implementation¶

Local dynamics is implemented in files ldy.h and ldy.c.

Off–diagonal blocks of \(\mathbf{W}_{\alpha\beta}\) (69), diagonal block \(\mathbf{W}_{\alpha\alpha}\) (69), and the entire \(\mathbf{U}=\mathbf{B}+\mathbf{W}\mathbf{R}\) system (62) are declared in ldy.h:39 as follows:

39typedef struct offb OFFB;

40typedef struct diab DIAB;

41typedef struct locdyn LOCDYN;

Off–diagonal blocks of \(\mathbf{W}_{\alpha\beta}\) (68) are declared in ldy.h:44 as follows:

44struct offb

45{

46 double W [9];

47 ...

48 DIAB *dia;

49 OFFB *n;

50};

Diagonal blocks of \(\mathbf{W}_{\alpha\alpha}\) (69) and free velocity \(\mathbf{B}_{\alpha}\) (67) are declared in ldy.h:53 as follows:

53struct diab

54{

55 double *R, /* average reaction ... */

58 W [9], /* diagonal block of W */

59 ...

60 B [3], /* free velocity */

63 OFFB *adj;

64

65 CON *con; /* the underlying constraint ... */

71 DIAB *p, *n;

78};

The local dynamics system is stored as a doubly linked list of diagonal blocs further pointing to singly linked lists of off–diagonal blocks in ldy.h:81 as:

81struct locdyn

82{

87DIAB *dia; /* list of diagonal blocks */

90};

Symbolic insertion of rows into \(\mathbf{W}\), without assembling of the numeric block values,

is administered by ldy.c:LOCDYN_Insert.

Similarly, deletion of rows from \(\mathbf{W}\) is administered by

ldy.c:LOCDYN_Remove.

Assembling of \(\mathbf{W}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\) is invoked by ldy.c:LOCDYN_Update_Begin.